“Our moral obligation is not to stop the future, but to shape it…to channel our destiny in humane directions and to ease the trauma of transition.”

- ALVIN TOFFLER, FUTURIST

There is no shortage of ideas for transforming the education system. In the past decade or so, we have witnessed a rising tide of consensus that the acquisition of knowledge is the floor of school performance, and we need to lift our sights higher—preparing our children with the habits of mind that will enable them to thrive in an unknowable future. The national conversation is (at last) shifting from, “How do we close the achievement gap?” to the deeper challenge of addressing the complexity of the relevance gap.

A growing number of school and district strategic plans now call for the nurturing of skills such as creativity, systems thinking, collaboration, and critical thinking. They call for a pedagogy that leans more on high-quality interdisciplinary project-based learning than siloed subjects delivered via lecture and assessed via rote memorization. These plans make a great deal of sense and articulate the essential skills necessary to thrive in an uncertain and ambiguous world. Too often though, adult behavioral change is either glossed over or not considered as a pivotal component of the implementation strategy.

In my work helping school leaders lead change, one of the biggest challenges a leader and their team face is the behavioral shift required to build and nurture the human ability to change. If a bold strategic plan stands a chance of being implemented, it is vital that the adult behavioral shifts are discussed, understood, and nurtured—all in service of the transformational vision laid out in the plan.

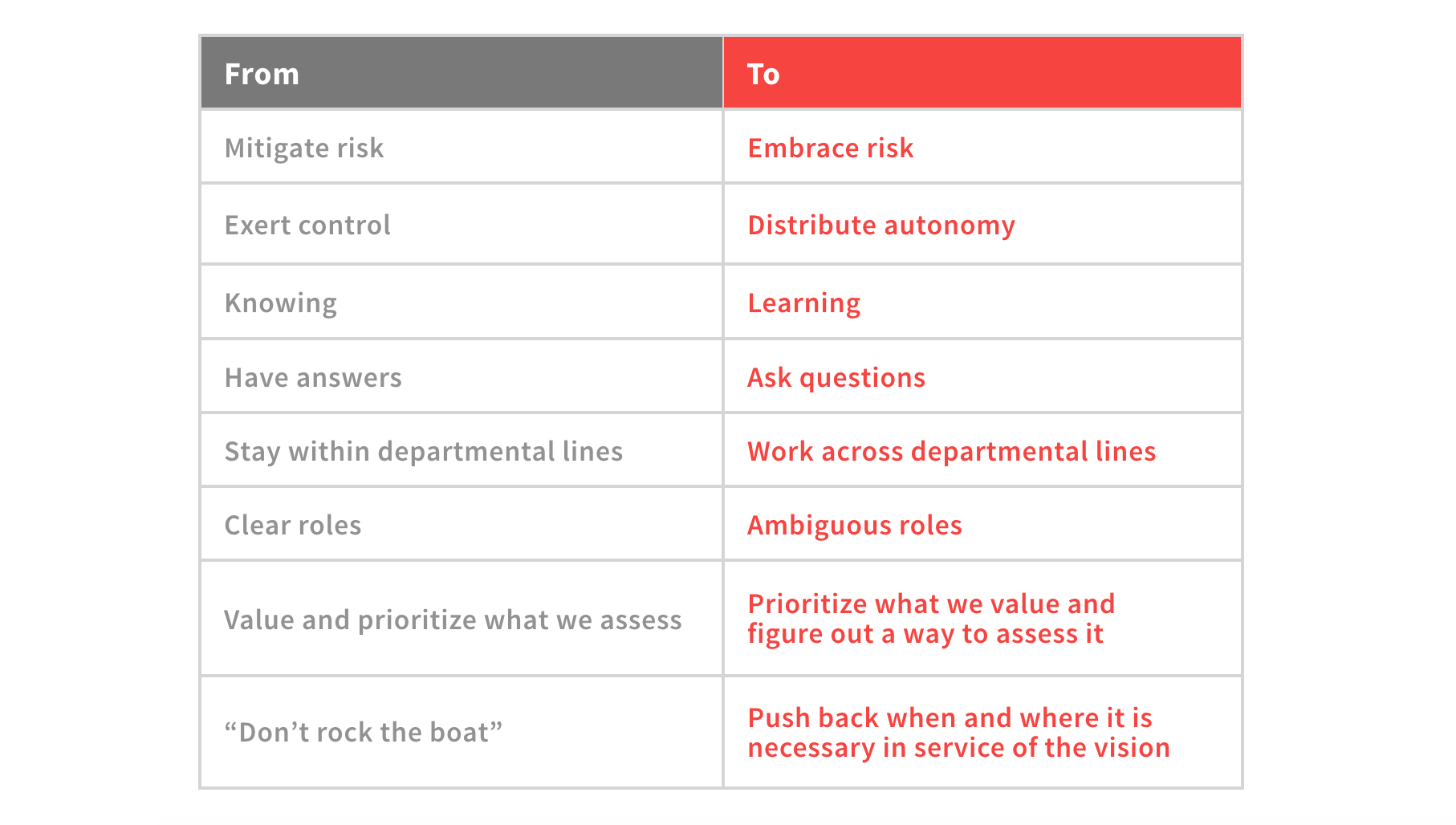

These are the most common behavioral shifts I have noticed in my work with leaders and teams implementing change in schools:

Does this resonate with your own experience? Are there shifts you would amend or add? I often think of the above as a continuum. Some situations might require us to lean more towards the left-hand column, and some to the right; but for the most part, the cultural norms of the industrial model of education lean heavily towards the left. We need to build our collective capacity to live more in the right-hand column.

At the core of this work of education transformation is adult transformation. The majority of us were raised in the old industrial system of education, and we find ourselves in the dual role of hospice worker to the old way and midwife to the new (Leicester 2013). It involves a shift away from the mental model of “How do I manage change resistance” to “How do I build change resilience?” This shift is critical.

It is highly unlikely that any five-year school strategic plan will be implemented with 100% fidelity and then enjoy a period of status quo once the plan’s goals have been achieved. Ongoing iterative changing—change that is meaningful and sustainable—is required.

One of the biggest obstacles of transforming the industrial model of education is the industrial model of management that underpins it—a model of command and control. Authority and autonomy are consolidated at the top with limited decision-making ability at the point of delivery (i.e. the relationship between teachers and students).

Is Change Management an Oxymoron

The Industrial era model of change management taught us that implementing change was a linear process. A group of senior leaders would gather around a boardroom table for several meetings to explore, discuss, and decide upon the strategic priorities of the organization. These priorities were then shared with the broader community, ideally resources were assigned, a solid communication plan was implemented to ensure that everyone understood the changes, and change would occur as per the timeline in the strategic plan.

There are (very) few circumstances when this linear approach to change works, but if you are leading the shift away from the industrial model of education, it is woefully inadequate to the task at hand. In their 2009 paper, “Building Organizational Change Capacity,” Anthony Buono and Ken Kerber unpack the complexity of change and identify two major factors to consider when leading change: organizational complexity and socio-technical uncertainty.

Organizational Complexity (vertical axis) refers to the intricacy of the system in which the change is to be implemented. Factors include organizational size, the number of services or programs offered, the extent to which different departments depend on each other for resources, and team interdependence to achieve desired results. The degree of complexity increases the more a change cuts across different departments and hierarchical levels, involves high levels of team interdependence, affects a range of services or programs, and requires the buy-in and support of a wide range of internal and external stakeholders.

Socio-Technical Uncertainty (horizontal axis) refers to the quantity and type of information processing and decision making required to implement the change. This is “based on the extent to which the tasks involved are determined, established or exactly known” (Buono and Kerber). If I am working in a traditional school and I want to shift from “Time-Based Learning” to “Mastery-Based Learning,” there is no cookie cutter model for me to pull off the shelf and implement. It involves an iterative cycle of working through what “I don’t know I don’t know” and a considerable amount of outreach, research, mini pilots, and learning by doing.